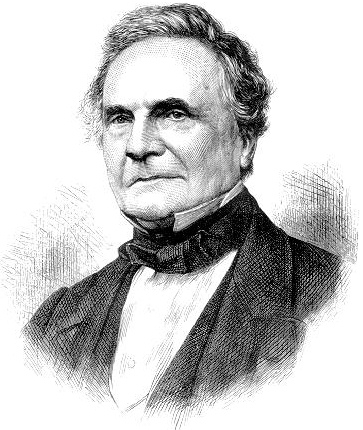

Charles Babbage citáty a výroky

Charles Babbage: Citáty anglicky

Zdroj: The Exposition of 1851: Views Of The Industry, The Science, and the Government Of England, 1851, p. 224

Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864), ch. 26 "Street Nuisances"

Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

"Passages from the life of a philosopher", The Basis Of Virtue Is Truth, p. 404-405

Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

Zdroj: The Exposition of 1851: Views Of The Industry, The Science, and the Government Of England, 1851, p. 51-52

Zdroj: The Exposition of 1851: Views Of The Industry, The Science, and the Government Of England, 1851, p. 225-226

Zdroj: The Exposition of 1851: Views Of The Industry, The Science, and the Government Of England, 1851, p. 173; As cited in: Samuel Smiles (1864) Industrial biography; iron-workers and tool-makers http://books.google.com/books?id=5trBcaXuazgC&pg=PA245, p. 245

"Passages from the life of a philosopher", Appendix, p. 489

Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

Zdroj: Reflections on the Decline of Science in England, and on Some of its Causes (1830), p. 3

That writers do not always mean the same thing when treating of miracles is perfectly clear; because what may appear a miracle to the unlearned is to the better instructed only an effect produced by some unknown law hitherto unobserved. So that the idea of miracle is in some respect dependent upon the opinion of man. Much of this confusion has arisen from the definition of Miracle given in Hume's celebrated Essay, namely, that it is the "violation of a law of nature." Now a miracle is not necessarily a violation of any law of nature, and it involves no physical absurdity. As Brown well observes, "the laws of nature surely are not violated when a new antecedent is followed by a new consequent ; they are violated only when the antecedent, being exactly the same, a different consequent is the result;" so that a miracle has nothing in its nature inconsistent with our belief of the uniformity of nature. All that we see in a miracle is an effect which is new to our observation, and whose cause is concealed. The cause may be beyond the sphere of our observation, and would be thus beyond the familiar sphere of nature; but this does not make the event a violation of any law of nature. The limits of man's observation lie within very narrow boundaries, and it would be arrogance to suppose that the reach of man's power is to form the limits of the natural world. The universe offers daily proof of the existence of power of which we know nothing, but whose mighty agency nevertheless manifestly appears in the most familiar works of creation. And shall we deny the existence of this mighty energy simply because it manifests itself in delegated and feeble subordination to God's omnipotence?

"Passages from the life of a philosopher", Appendix: Miracle. Note (A)

Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

This is not the place to argue that great question. It is sufficient to remark, that the best-informed and most enlightened men of all creeds and pursuits, agree that truth can never damage truth, and that every truth is allied indissolubly by chains more or less circuitous with all other truths; whilst error, at every step we make in its diffusion, becomes not only wider apart and more discordant from all truths, but has also the additional chance of destruction from all rival errors.

Zdroj: The Exposition of 1851: Views Of The Industry, The Science, and the Government Of England, 1851, p. 225