„Mám pocit, že by to byl téměř výsměch, dostat Nobelovu cenu a účastnit se slavnostního předání.“

Zdroj: [Hargittai, Istvan, 2002, The road to Stockholm: Nobel Prizes, science, and scientists, 26, en, 0-19-860785-7]

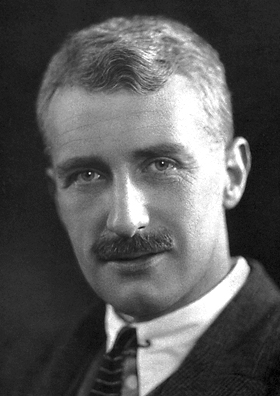

Archibald Vivian Hill byl anglický fyziolog, spoluzakladatel řady odvětví biofyziky a operačního výzkumu. Za objevy v oblasti tvorby tepla ve svalech získal roku 1922 Nobelovu cenu za fyziologii a lékařství, spolu s ním byl toho roku oceněn také Otto Fritz Meyerhof.

A. V. Hill studoval v Cambridge na Trinity College a na univerzitě zůstal i po absolutoriu. Objevil řadu zákonitostí ve fyziologii a spolu s Hermannem Helmholtzem bývá považován za otce biofyziky. V roce 1914 vstoupil do armády, kde kolem sebe shromáždil tým špičkových vědců, který položil základy operačního výzkumu. Po válce se vrátil do Cambridge, ale již roku 1920 přešel na Viktoriinu univerzitu v Manchesteru, kde se stal profesorem fyziologie a svým výzkumem pomohl vyjasnit funkci svalů. Roku 1923 se stal profesorem na University College v Londýně, kde setrval až do emeritování roku 1951. Ve vědecké práci pokračoval až do roku 1966.

Podílel se také na politickém životě Británie a organizaci vědy. Významná je jeho činnost v charitativní organizaci Academic Assistance Council, která se ujímala vědců ohrožených Hitlerovým režimem a asi 900 jich zachránila.

Wikipedia

„Mám pocit, že by to byl téměř výsměch, dostat Nobelovu cenu a účastnit se slavnostního předání.“

Zdroj: [Hargittai, Istvan, 2002, The road to Stockholm: Nobel Prizes, science, and scientists, 26, en, 0-19-860785-7]

The Ethical Dilemma Of Science, Hill, 1960. The Ethical Dilemma of Science and Other Writings https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=zaE1AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false. Rockefeller Univ. Press, pp. 88-89

The Ethical Dilemma of Science and Other Writings https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=zaE1AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (1960, Cap 1. Scepticism and Faith, p. 41)

The Ethical Dilemma of Science and Other Writings https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=zaE1AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (1960, Cap 1. Scepticism and Faith, p. 41)