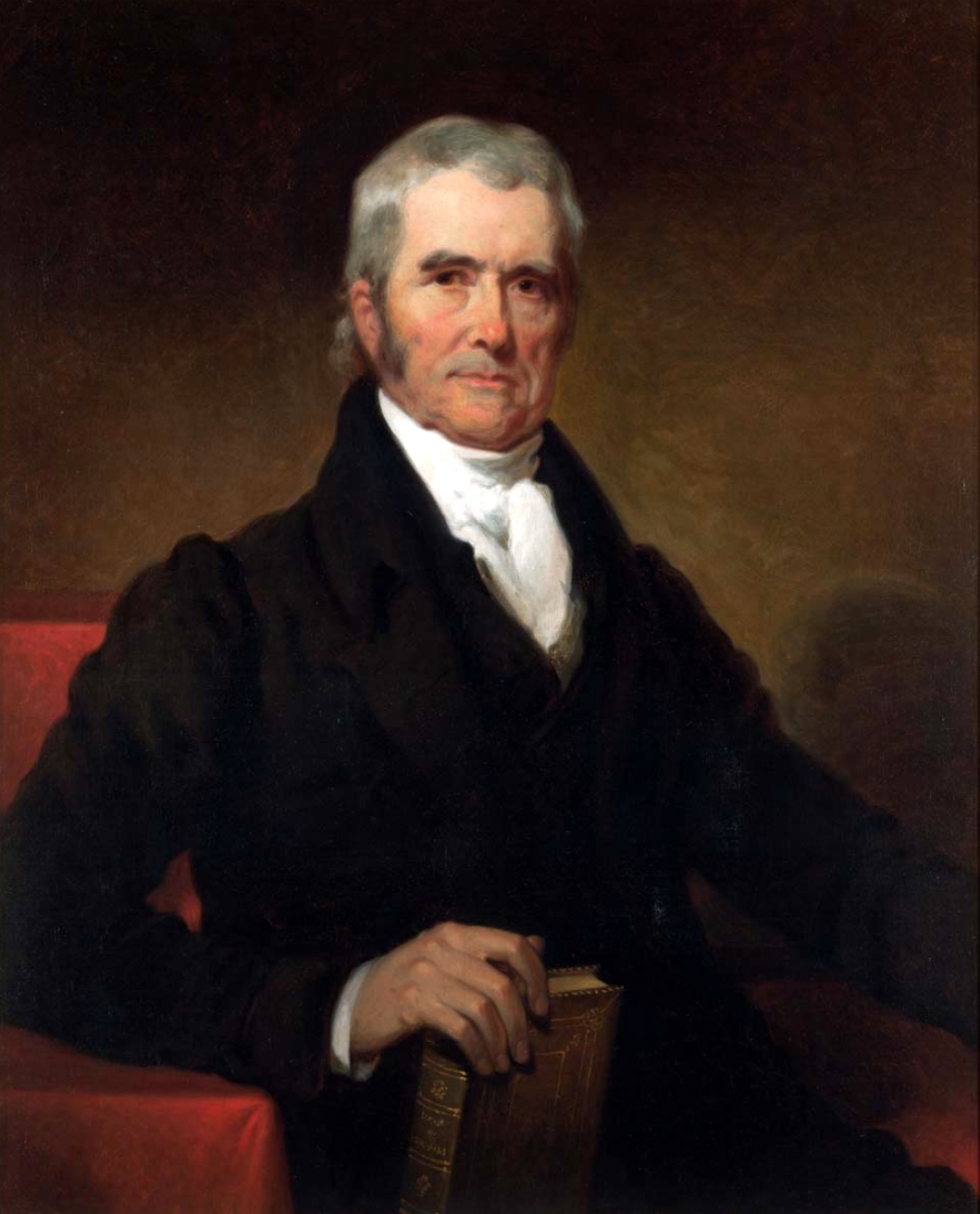

John Marshall citáty a výroky

John Marshall: Citáty anglicky

Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. (6 Wheaton) 264, 387 (1821)

17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 405

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

5. U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 177

Marbury v. Madison (1803)

Reportedly said to a young John Bannister Gibson, who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, when Gibson remarked that Marshall had reached the acme of judicial distinction; in David Goldsmith Loth, Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Growth of the Republic (1949), p. 275. See also Albert J. Beveridge, "Life of John Marshall" (1919)

17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 424

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

Kontext: [.. ] it can scarcely be necessary to say that the existence of State banks can have no possible influence on the question. No trace is to be found in the Constitution of an intention to create a dependence of the Government of the Union on those of the States, for the execution of the great powers assigned to it. Its means are adequate to its ends, and on those means alone was it expected to rely for the accomplishment of its ends. To impose on it the necessity of resorting to means which it cannot control, which another Government may furnish or withhold, would render its course precarious, the result of its measures uncertain, and create a dependence on other Governments which might disappoint its most important designs, and is incompatible with the language of the Constitution. But were it otherwise, the choice of means implies a right to choose a national bank in preference to State banks, and Congress alone can make the election. After the most deliberate consideration, it is the unanimous and decided opinion of this Court that the act to incorporate the Bank of the United States is a law made in pursuance of the Constitution, and is a part of the supreme law of the land.

17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 409 and 416-418. Regarding the Necessary and Proper Clause in context of the powers of Congress.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

“We must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding.”

17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 407

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

22 U.S. (9 Wheaton) 1, 188

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 407

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)