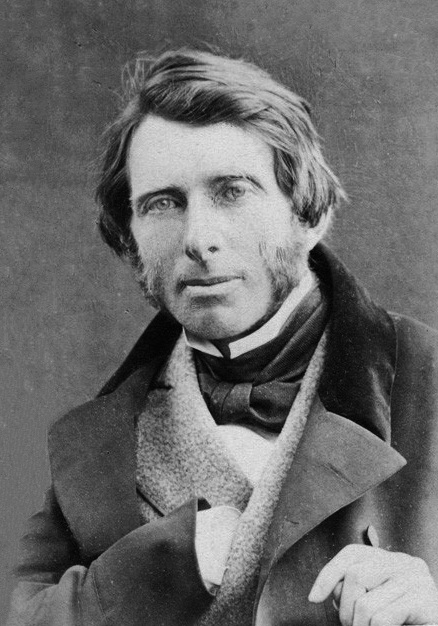

John Ruskin nejznámější citáty

John Ruskin: Citáty o lidech

John Ruskin: Citáty o moudrosti

John Ruskin citáty a výroky

„Není nic podivnějšího, než když lidé uznávají poctivost ve hře, ale nikoliv v práci.“

Zdroj: Magazín Dnes + TV. Praha: MaFra, a.s., 2007, roč. XV, č. 13. ISSN 2533-6932.

John Ruskin: Citáty anglicky

Volume III, part IV, chapter XVI (1856).

Modern Painters (1843-1860)

The Crown of Wild Olive, lecture IV: The Future of England, section 151 (1866).

He chooses work for every creature which will be delightful to them, if they do it simply and humbly. He gives us always strength enough, and sense enough, for what He wants us to do; if we either tire ourselves, or puzzle ourselves, it is our own fault. And we may always be sure, whatever we are doing, that we cannot be pleasing Him, if we are not happy ourselves.

P. 123

Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895)

“The entire vitality of art depends upon its being either full of truth, or full of use”

Lecture IV

Lectures on Art (1870)

Kontext: The entire vitality of art depends upon its being either full of truth, or full of use; and that, however pleasant, wonderful, or impressive it may be in itself, it must yet be of inferior kind, and tend to deeper inferiority, unless it has clearly one of these main objects, — either to state a true thing, or to adorn a serviceable one.

“When men are rightly occupied, their amusement grows out of their work”

Sesame and Lilies.

Kontext: When men are rightly occupied, their amusement grows out of their work, as the colour-petals out of a fruitful flower;—when they are faithfully helpful and compassionate, all their emotions become steady, deep, perpetual, and vivifying to the soul as the natural pulse to the body. But now, having no true business, we pour our whole masculine energy into the false business of money-making; and having no true emotion, we must have false emotions dressed up for us to play with, not innocently, as children with dolls, but guiltily and darkly.

“The purest and most thoughtful minds are those which love colour the most.”

Volume II, chapter V, section 30.

Zdroj: The Stones of Venice (1853)

“He who has the truth at his heart need never fear the want of persuasion on his tongue.”

Volume III, chapter II, section 99.

The Stones of Venice (1853)

Zdroj: The Stones of Venice: Volume I. The Foundations

Zdroj: Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895), P. 269.

“In painting as in eloquence, the greater your strength, the quieter your manner.”

Volume V, part VIII, chapter III (1860).

Modern Painters (1843-1860)

“To banish imperfection is to destroy expression, to check exertion, to paralyze vitality.”

Zdroj: The Stones of Venice

Essay I: "The Roots of Honour," section 29.

Unto This Last (1860)

Kontext: “I choose my physician and my clergyman, thus indicating my sense of the quality of their work.” By all means, also, choose your bricklayer; that is the proper reward of the good workman, to be “chosen.” The natural and right system respecting all labour is, that it should be paid at a fixed rate, but the good workman employed, and the bad workman unemployed. The false, unnatural, and destructive system is when the bad workman is allowed to offer his work at half-price, and either take the place of the good, or force him by his competition to work for an inadequate sum.

Sesame and Lilies.

Kontext: When men are rightly occupied, their amusement grows out of their work, as the colour-petals out of a fruitful flower;—when they are faithfully helpful and compassionate, all their emotions become steady, deep, perpetual, and vivifying to the soul as the natural pulse to the body. But now, having no true business, we pour our whole masculine energy into the false business of money-making; and having no true emotion, we must have false emotions dressed up for us to play with, not innocently, as children with dolls, but guiltily and darkly.

Praeterita, volume I, chapter IX (1885-1889).

Kontext: My entire delight was in observing without being myself noticed,— if I could have been invisible, all the better. I was absolutely interested in men and their ways, as I was interested in marmots and chamois, in tomtits and trout. If only they would stay still and let me look at them, and not get into their holes and up their heights! The living inhabitation of the world — the grazing and nesting in it, — the spiritual power of the air, the rocks, the waters, to be in the midst of it, and rejoice and wonder at it, and help it if I could, — happier if it needed no help of mine, — this was the essential love of Nature in me, this the root of all that I have usefully become, and the light of all that I have rightly learned.

Praeterita, volume I, chapter IX (1885-1889).

Kontext: My entire delight was in observing without being myself noticed,— if I could have been invisible, all the better. I was absolutely interested in men and their ways, as I was interested in marmots and chamois, in tomtits and trout. If only they would stay still and let me look at them, and not get into their holes and up their heights! The living inhabitation of the world — the grazing and nesting in it, — the spiritual power of the air, the rocks, the waters, to be in the midst of it, and rejoice and wonder at it, and help it if I could, — happier if it needed no help of mine, — this was the essential love of Nature in me, this the root of all that I have usefully become, and the light of all that I have rightly learned.

Lecture II, section 35.

The Eagle's Nest (1872)

Kontext: We shall be remembered in history as the most cruel, and therefore the most unwise, generation of men that ever yet troubled the earth: — the most cruel in proportion to their sensibility, — the most unwise in proportion to their science. No people, understanding pain, ever inflicted so much: no people, understanding facts, ever acted on them so little.

“You must either make a tool of the creature, or a man of him.”

Volume II, chapter VI, section 12.

The Stones of Venice (1853)

Kontext: You must either make a tool of the creature, or a man of him. You cannot make both. Men were not intended to work with the accuracy of tools, to be precise and perfect in all their actions. If you will have that precision out of them, and make their fingers measure degrees like cog-wheels, and their arms strike curves like compasses, you must unhumanize them. All the energy of their spirits must be given to make cogs and compasses of themselves…. On the other hand, if you will make a man of the working creature, you cannot make him a tool. Let him but begin to imagine, to think, to try to do anything worth doing; and the engine-turned precision is lost at once. Out come all his roughness, all his dulness, all his incapability; shame upon shame, failure upon failure, pause after pause: but out comes the whole majesty of him also; and we know the height of it only when we see the clouds settling upon him.

Volume II, chapter VI, section 42.

The Stones of Venice (1853)

Kontext: We are to remember, in the first place, that the arrangement of colours and lines is an art analogous to the composition of music, and entirely independent of the representation of facts. Good colouring does not necessarily convey the image of anything but itself. It consists of certain proportions and arrangements of rays of light, but not in likeness to anything. A few touches of certain greys and purples laid by a master's hand on white paper will be good colouring; as more touches are added beside them, we may find out that they were intended to represent a dove's neck, and we may praise, as the drawing advances, the perfect imitation of the dove's neck. But the good colouring does not consist in that imitation, but in the abstract qualities and relations of the grey and purple.